Follow The Money:

With cash we advance, and with cash we get repaid

ABL industry veteran, Joseph lannuccilli makes a strong case for the need to focus on tracking the nature of individual cash payments. To detect fraud early, he recommends a “Top 10 List” to monitor cash activity.

A fundamental tool for monitoring asset quality and managing risk management is the concept of “following the money.” By that, I mean evaluating the borrower’s policies and procedures, both in-house and in the field, regarding handling cash.

In the face of lingering weakness in the economy, asset-based borrowers continue to have difficulties making payroll and paying important suppliers for critical goods and services. Asset-based lenders may enjoy long-term relationships with their clients, built on trust, but a company may hit a rocky road when liquidity tightens. Its lender may be unwilling to extend more funds, and thus it may have to resort to other means.

That’s why “catching a thief” at an early stage is the most important aspect of maintaining stability in the lender’s bottom line. There are many ways for borrowers to mislead us through fictitious reporting, but there are many ways to detect and deal with it, too. The details surrounding customer checks, wires and their proper application are often keys to detecting fraud at an early stage both in-house and during field examinations. Following are the top ten issues surrounding cash irregularities or weakness in collateral.

1) Lags in Applying Cash

A lag in crediting AIR could mean that eligible receivables are overstated. In particular, the deposit date in the lockbox or blocked account should coincide with the application date in the client’s system. Otherwise, the borrower is paying down the loan but has not purged corresponding invoices from its receivables and borrowing base.

2) Advance Deposits

The borrower may negotiate terms under which its customer furnishes a deposit prior to billing. The borrower may account for these funds as liabilities on the balance sheet and not apply them to the customer’s outstanding balances. This creates a contra offset in the event of liquidation.

3) Automatic Application to Oldest Invoice

Here, the borrower applies customer payments to the oldest invoices in the system. Reviewing summary agings will not detect this. Only a review of a detailed aging report will indicate this. In this scenario, open invoices in the eligible columns may have exact payment amounts credited to the ineligible column(s). Similarly, “on-account payments” are typically applied to the oldest invoices. They occur when the account debtor pays an even amount that is applicable to no specific invoice. This could be a sign of the customer’s financial weakness, or it could be a sign that the borrower overstated the original invoices and the customer is paying a lesser amount.

4) Short Payments

Account debtors may make payments that are lower than the original invoice. The customer may be taking discounts, allowances and other deductions that the borrower leaves open when applying the cash, thereby overstating collateral. Short payments could be an indication that the customer’s invoices are lower than the amounts recorded on the aging report.

5) Skipped Payments

This occurs when a customer pays a newer invoice before paying an older invoice. This usually means that the customer is disputing the older invoice or simply does not recognize the liability to the borrower.

6) Wrong Dates

The date on the customer’s remittance advice or check stub should correspond to the borrower’s detailed aging report. If the customer’s date is later than the aging date, some form of prebilling or other revenue recognition issue may exist.

7) Mismatched Customer Names

Reviewing the detail on customer payments can reveal that payments are actually from third parties, not the customers on the aging report. These can tie from an affiliate company or fictitious company and should not be eligible collateral. It can also be an indication of kiting of funds.

8) Redeposited NSF Checks

This may be an indication of account debtor weakness if its original payment was returned for insufficient funds.

9) Conversion of Cash

In a non-notification financing arrangement, it’s easier for the borrower to divert funds from the lockbox account to an operating account, thereby gaining use of the lender’s collateral. The borrower may be building a war chest for a Chapter 11 financing or simply using the cash for other purposes. The lender should routinely monitor the borrower to ensure that a reasonable amount of funds are flowing each day into the lockbox or blocked account. Intra-month turnover calculations are another vehicle to uncover this.

10) Kiting of Funds

This is the biggest potential nightmare for a lender. Major frauds have occurred when borrowers transfer funds to and from bank accounts they own or control, thereby gaining float time and the use of uncollected funds. Here’s how it works. To generate cash availability, the borrower creates fictitious invoices and includes them as eligible receivables in its borrowing base. Individual billings may be either to an actual customer or to a dummy corporation owned by the principal(s). If the invoices are going to normal customers, a company that is kiting funds will not send those invoices to the debtor. In either method, the dummy corporation becomes the source of kited funds used to pay the fictitious invoices before they reach ineligible status. This pattern can continue ad infinitum until discovery is made.

Classic Case

Here is an illustration of clearly fraudulent activity. If not detected early, the fraud could mushroom and result in the most disastrous of all events: a bad-debt write-off.

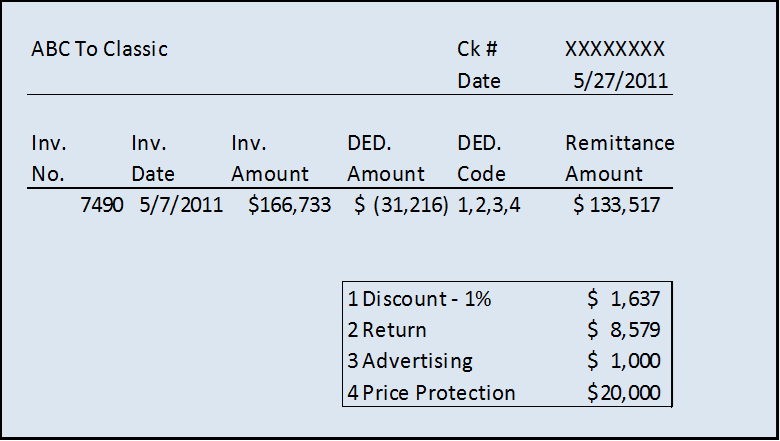

Here is a remittance advice (check stub) paid to a borrower, named “Classic” from its customer, “ABC.”

Fact 1: Effective on 4-2-11, the asset-based lender had advanced 85% of $166,733, or $141,723 against the original invoice.

Fact 2: The customer’s check dated 5-27-11 was remitted to the borrower. The borrower immediately deposited the check as “Non AIR cash only,” thereby picking up full borrowing availability on an additional $133,517. The deposit should have been classified as a receivable payment. In effect, the borrower did not purge the invoice in its accounting system until later.

Fact 3: The customer check indicates that it recognized the invoice on 5-17-11, not 4-2-11. That’s approximately a month and a half after the borrower’s date, a clear indication of prebilling.

Fact 4: The customer received 1%/10 Net 30 terms from the shipping date of 5-17-11, not 75-day terms from the prebilled invoice dated 4-2-11.

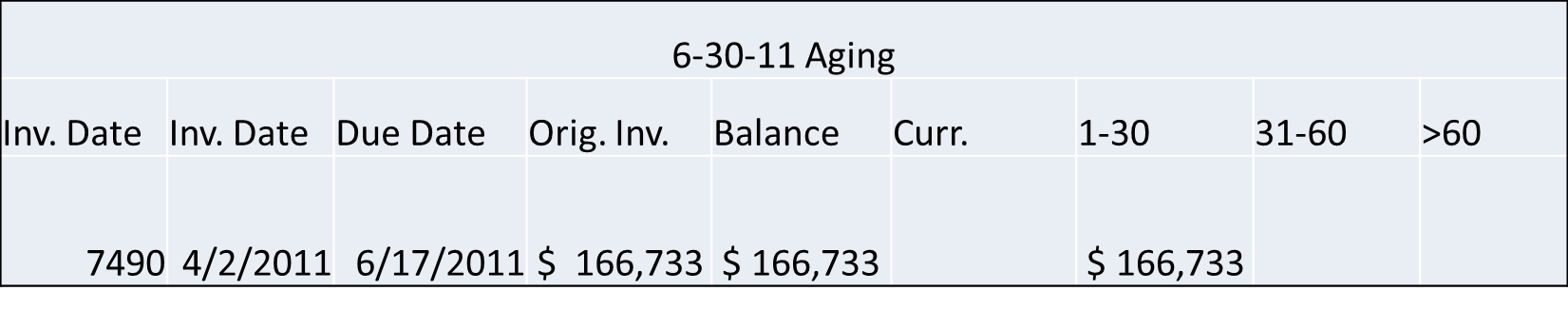

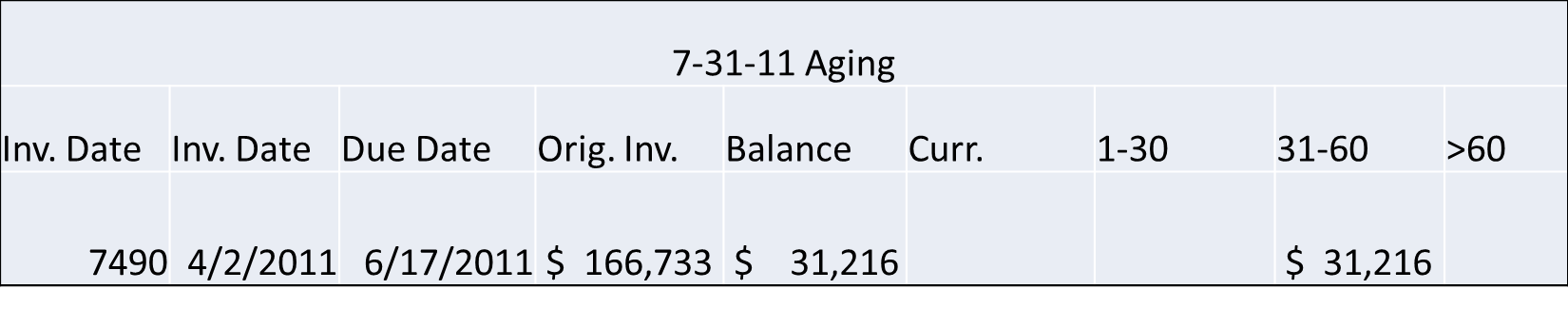

Fact 5: Several days later and during July 2011, the borrower partially covered itself by applying the net cash amount received from the May 2011 check. The borrower left open the $31,216 uncollectable deduction taken by ABC.

Fact 6: The Price Protection deduction of $20,000 indicates that the product didn’t sell through at suggested retail prices and that the customer is authorized to mark the product down (and pass this along to the borrower).

Fact 7: The deduction of $8,579 for returned products is an indicator that the borrower is waiting for the customer to take the deduction rather than issuing credit memos in a timely manner.

Fact 8: The borrower repeats this pattern with other customers. Another illustration is a comparable January and February “due date” aging for the borrower’s account debtor, ABC. Note that the $31,216 is not only uncollectable; it would be aged in the over-60-day ineligible column if the correct 30-day terms were in the accounting system instead of the 45-day terms reported in the aging.

CONCLUSION

Many asset-based lenders do not have the resources to ramp up cash monitoring in all credits. At the same time, it’s critical to do so when red flags such as turnover and dilution deteriorate to the point of concern.

We cannot prevent fraud from occurring, however, we can detect it early. With appropriate management, we can eliminate larger write-offs in our industry. That’s why vigilant cash monitoring is an element of the ongoing diligence that an asset-based lender should include in its standard policies and procedures. Follow the money.

Article featured in the Secured Lender, published July/August 2011